I hardly watch movies except when someone forces me to, or there is a strong trigger to watch. Last week, following the AR Rahman PR fiasco, I was tempted to revisit his music, rediscovered Taal, and in a jiffy, decided to watch it. I had watched it when it was released. I was in school, crushing hard on Aishwarya, and vaguely remembered it being termed “female-centric.” Twenty-five years later, I was curious: what did a “female-centric” movie in 1999 actually look like?

Turns out, it looked like four men’s egos playing football with a woman’s naivety and vulnerability.

The Plot: A Masterclass in Male Entitlement

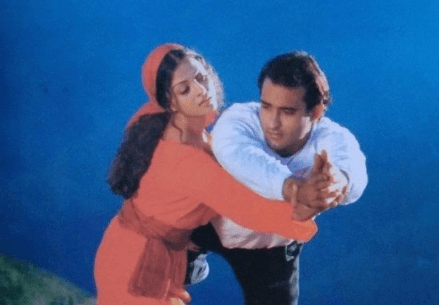

Mansi is a girl who has always remained within the family and hasn’t known men outside her family. Manav sees her, clicks her pics without consent, and creates situations to spend time with her.

Jagmohan manipulates his way to get access to important people in Chamba through Tara Babu, Mansi’s father, who is a proud man.

No one stops Manav from getting involved with Mansi till their work is getting done. After Manav leaves with family, Tara Babu discovers Mansi’s affair. He visits Jagmohan without prior information and expects to be treated as a friend, but that doesn’t happen. Family members, including Manav’s aunt, taunt the father and daughter. Arguments escalate. Tara Babu slaps Jagmohan.

Manav is angry and insults Tara Babu and Mansi. Enraged, Mansi breaks up with him. Then the father and daughter are discovered by Vikrant Kapoor, who signs Mansi as his lead singer and performer.

Vikrant is weird and has a condition that, for the next three years, Mansi is not allowed to be in a relationship or marry. That’s fine, I guess.

Meanwhile, Manav realizes it wasn’t Tara Babu’s mistake and wants to get back together with Mansi. He tries once, but Mansi rejects him. Hereafter, Manav takes up the challenge that he would not take any extreme steps, but still, everyone around him would bring Mansi to him.

Manav keeps meeting Mansi and discourages her from becoming the star she is. He reminds her that it’s not her but her ego that has agreed to pursue a career as a singer and dancer.

Vikrant, being a nosy boss, keeps pressing Mansi to reveal details about Manav. When she gets fed up, shouts at him, and leaves the job, Vikrant gets angry. Later, it’s Mansi who apologizes and comes back. Then Vikrant decides to marry her and, without telling her, sends a proposal to Tara Babu.

Tara Babu emotionally blackmails Mansi to accept the relationship. Vikrant knows she doesn’t love him but goes ahead with the relationship anyway.

After Manav jumps into the fire to save Mansi’s scarf, Jagmohan realizes his mistake and apologizes to Tara Babu. Now both old men are friends, and they make Mansi guilty about marrying Vikrant, along with Manav. Eventually, Vikrant is the one who asks Mansi to marry Manav because, of course, he feels he is losing this battle because everyone is emotionally manipulating him now.

So, you see, the only decision that Mansi actually takes in the entire movie is to break up with Manav. In my opinion, it was the best decision, and had Mansi been given agency, this movie wouldn’t have been made.

I also remember how my mother was upset with this movie and blamed Mansi for being a bad daughter for forgiving Jagmohan. And now, after rewatching the movie, I cannot help but question the misogyny we inherit in our childhood. This is how society controls women: by making them do things and shifting the blame to them.

The Bitter Aftertaste

Taal wasn’t just a film. It was a mirror reflecting the world I grew up in. The patterns I saw on screen weren’t fictional—they were the same scripts playing out in homes, schools, and families around me. When I started connecting the dots between Mansi’s story and the real lives of women I knew, the parallels were impossible to ignore.

When I translate the movie to everyday real-life scenarios, I found these patterns I observed over the last 25 years:

Even though I was in a co-ed school, most of my girlfriends were not allowed to talk to boys. Getting a call at home from a boy was considered inappropriate and guaranteed punishment or silent treatment.

Most parents felt entitled enough to own their children’s lives. I remember one of my classmates, when caught with her boyfriend, was forcibly married to an older man within a week, while she was not even 18.

Love marriages are frowned upon because relationships between men and women are often reduced to physical intimacy, and women in love become impure and not experienced or mature enough to take their own decisions.

Showing up and showing off is the love language when it comes to bigger extended families, even at the cost of the children’s safety. I have a few friends (some of whom I met in therapy) talking about being inappropriately touched or violated by uncles and cousins while their parents denied to back them up.

My friend was told by her future family that they preferred to have a daughter-in-law who stayed at home. However, since they were so “progressive,” they would allow her to work, but she needs to finish all the domestic chores first because what is career for women, if not a hobby. Of course, the salary belongs to them.

My father’s friend’s wife died during childbirth. She had always known bearing children would put her life at risk, but she preferred to die than to be known as “barren.”

The Verdict

As one of my friends always tells me, “That was a 1999 movie. What do you expect?”

I would say, exactly this. A faulty storyline that gives me a reason to write a blog in 2026. This “female-centric” movie (termed so because the lead female character was given maximum screen time since she was a beauty pageant winner and a natural charmer; still a fan) stirred many emotions and brought bitter memories. But perhaps that’s the point. Perhaps we need these reminders of how far we haven’t come, dressed up in gorgeous cinematography and AR Rahman’s timeless music.

The only thing “female-centric” about Taal was Aishwarya Rai’s face on the poster.

Well reflected and penned down . All our heart💝 needs repair .

LikeLike